What Shipwrecks Teach Us About South Coast Resilience

The ocean has always been a rough historian.

Along the stretch of New South Wales coastline between Wollongong and Eden, wreckage lies just beneath the waves, timber bones, rusted ribs, a stern plate marked with salt and loss. To walk the beaches here, or dive beneath them, is to move through memory. And yet, these aren’t just maritime tragedies. They are local lessons in resilience, architecture in reverse.

Once upon a time, NSW coastal shipping was described as “a scheme for manufacturing widows and orphans.” More than 300 ships were lost between Sydney and the Victorian border. The South Coast, with its reef-laced shores, sudden southerlies, and shifting sands, is one of the most wreck-dense regions in the country. But the story doesn’t end in saltwater.

Before road or rail, shipping was the lifeline.

Towns like Kiama, Eden and Batemans Bay depended on coastal vessels for coal, blue metal, timber, correspondence, kin. But the very waters that connected them also claimed them.

Weather fronts move fast here and back then navigation was imprecise. Currents misread could mean disaster.

And the land? Beautiful but brutal. There are more cliffs, coves, rock shelves and shoals than there are gentle edges.

The SS Bombo: a steel-hulled freighter hauling basalt from Kiama in 1949, caught in a sudden gale off Port Kembla, the loose cargo shifted. The vessel listed violently and capsized and of the fourteen crew aboard, only two survived. Today, the wreck lies 8 kilometres offshore, a dive site and memorial, its story inscribed on a plaque overlooking Black Beach. It’s not just a story from the past. Its local ground marked by loss.

Wrecked beneath the cliffs of Green Cape in 1886 Ly-ee-Moon struck the reef at full speed despite good visibility. Eighty-six people were on board. Fifteen survived. Among the dead: Flora MacKillop, mother of Mary MacKillop. Recovery teams buried the bodies near the still-standing lighthouse, unmarked graves in shifting sand. This collision was felt through generations.

Then there’s the 1797 saga of the Sydney Cove. After the ship was wrecked off Preservation Island, a longboat of 17 men set out to reach Sydney. The longboat itself was wrecked on Ninety Mile Beach. What followed was a gruelling overland journey of more than 600 km along the coastline. Only three survived. During that walk, William Clark noted coal in the cliffs near Coalcliff, helping cement this journey as one of the earliest European crossings of the South Coast. These wrecks although tragic, reveal how people adapt when the path is gives way beneath them.

For many towns along the South Coast, these wrecks aren’t cautionary tales. They are identity. They are place. The wreck of the Nancy in 1805 still echoes near Jervis Bay, where a split mainsail and storm surge grounded her at night. The crew walked to Sydney. One drowned. The skins she carried, 3,787 of them, never made it to market, but her story still surfaces, in museum archives and memory.

These events shaped more than shipping routes. They catalysed lighthouses, coastal planning, community rituals. Some of the most stunning beacons along this stretch, like Green Cape Lighthouse , were built because of repeated tragedy. That light still flashes, not just to guide ships, but to remind us of what’s been lost.

In 2025, we talk a lot about resilience. About mental load, about nervous system regulation, about building a life that withstands.

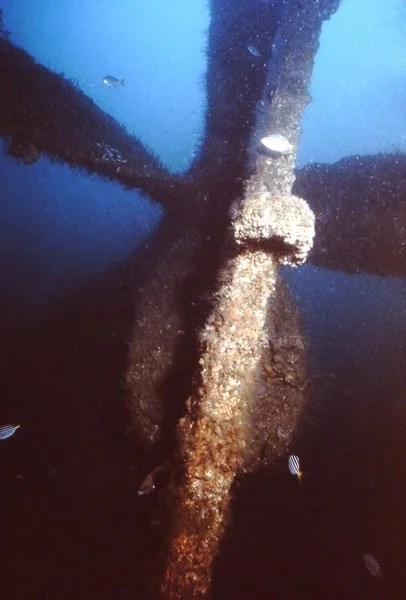

But resilience isn’t always as obvious, sometimes it’s buried. Sometimes it lies 30 metres below the surface, rusted and reefed, quietly hosting marine life. Sometimes it’s a plaque on a headland, or a museum tucked beside the wharf. Sometimes it’s a local diver who pauses in reverence when swimming over the Bombo.

Shipwrecks teach us that endurance doesn’t mean avoiding impact, it means rebuilding smarter. It means memory that protects, not paralyses.

These coastal communities didn’t flee. They adapted. They kept shipping. They built light on rock. They buried their dead with dignity and kept living by the tide.

To stand on the shore between Wollongong and Eden is to feel something old stir, something broken, but not gone. The coast has always been a teacher, if we’re willing to read what it writes in wreckage.

So here’s the question we’re left with: when life gets turbulent, when your path disappears, what do you hold onto?

Do you have a shipwreck story in your community? Write to us — we’d love to feature it in a future edition.